How much Pupil Premium funding are primary schools missing out on?

In 2013/14, primary schools shared over one billion pounds in deprivation Pupil Premium funding. Based on the January 2013 school census, 1.1 million (27%) primary-age pupils were found to be eligible for deprivation Pupil Premium funding, on the basis for having been eligible for free school meals at some point in the previous six years. This equated to an extra £953 per eligible pupil.

By the 2017/18 academic year, the per pupil amount had risen to £1,320. There were still around 1.1 million eligible pupils in primary schools, so the total amount of funding had risen to £1.4 billion.

However, the total number of pupils had risen by half a million, meaning that the percentage eligible for deprivation funding had fallen to 24%. (As we wrote here, London is the region most affected.)

There are two reasons for this. Firstly, a general fall in free school meals eligibility, presumably due to changes in the economy and changes to benefit eligibility. Secondly, the introduction of universal infant free school meals (UIFSM) in September 2014.

How much funding are primary schools missing out on?

First a simple calculation. If the percentage of primary pupils eligible for deprivation funding in 2017/18 had remained the same as in 2013/14 – 27% – then an extra 137,000 pupils would have been eligible. At 2017/18 rates, this would have meant an additional £181 million in funding.

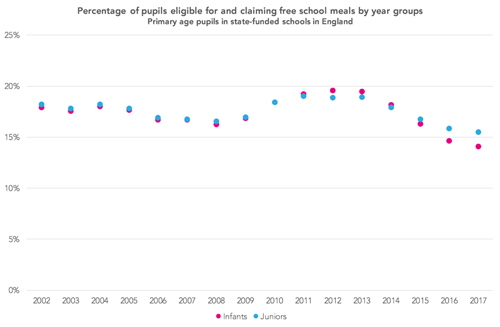

Now let’s try to separate out the impact of UIFSM from the general downward trend in free school meals eligibility. The chart below compares how the FSM eligibility rate has changed among pupils in the infant years (Reception to Year 2) and those in the junior years (Year 3 to Year 6).

As can be seen, the dots for infants start to fall below the dots for juniors from 2015, the first year of UIFSM.

So despite the best efforts of schools to collect evidence of eligibility for free school meals from the parents of infant children after the introduction of UIFSM, it appears that a small percentage of parents did not respond.

Estimating the impact of UIFSM

We need some sort of estimate of what the percentage of eligible pupils would have been in the absence of the UIFSM policy.

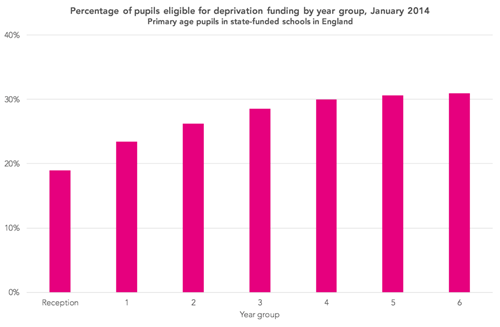

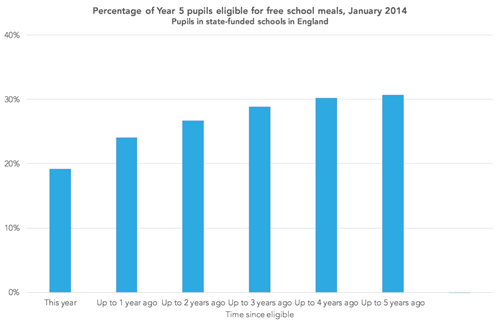

The first chart below shows the percentage of pupils in each year group eligible for deprivation funding in January 2014, before the introduction of UIFSM, while the second shows the percentage of pupils in Year 5 in January 2014 who were eligible for free school meals over different time intervals.

The pattern in the two charts broadly matches, as it does in the 2013 data. The significance of this is that we can use what we know about when pupils in Year 5 in January 2017 were eligible for free school meals to estimate what Pupil Premium eligibility would have been for younger pupils in January 2017 in the absence of the UIFSM policy.

The Year 5 group would have been the youngest cohort in 2016/17 not to have been affected by UIFSM. Using the relationship established in January 2014, we can use the percentage of pupils known to be eligible for free school meals during 2016/17 to give us an estimate of the percentage of Reception pupils eligible for deprivation funding. Similarly, the percentage of Year 5 eligible for free school meals in 2016/17 or the previous year gives us an estimate for Year 1 and so forth.

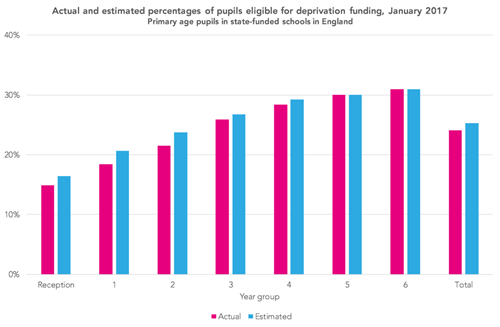

Doing this, the chart below shows actual and estimated percentages of pupils eligible for deprivation funding in January 2017.

In total, an extra 51,000 pupils might have been eligible for deprivation funding in 2017/18 – just over 1% of pupils. At the prevailing rate, this amounts to £67 million in funding.

And of course, the percentage of pupils eligible for deprivation funding fell further (to 23.3%) in January 2018 and so the amount of missing funding for 2018/19 would have increased.

Perhaps the total deprivation funding pot would have remained the same even if the Pupil Premium eligibility rate had stayed the same, in effect reducing the per pupil amount and spreading the jam a bit thinner.

But it does appear that some schools will be missing out on Pupil Premium funding as a result of universal infant free school meals. Not huge amounts of money, but enough for a few little extras.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Follow us on Twitter to get all of our research as it comes out.

About the Author: Dave Thomson

Dave Thomson is chief statistician at FFT with over fifteen years’ experience working with educational attainment data to raise attainment in local government, higher education and the commercial sector. His current research interests include linking education and workplace datasets to improve estimates of adult attainment and study the impact of education on employment and benefits outcomes.